|

BIRTH OF MODERN WELL LOGS

BIRTH OF MODERN WELL LOGS

All the

logs mentioned so far, except the caliper, needed a conductive fluid in the

borehole in order to operate. The induction log was introduced in 1949 to

overcome this requirement in holes drilled with air or oil based drilling mud.

The log was calibrated to read rock conductivity by inducing currents with

electromagnetic coils. Prior to this invention, logging tools impressed currents

into the formation by means of direct application of voltages from the logging

tool electrodes. Over the next ten years, the induction log also became popular

in wells drilled with fresh mud.

Henry

Doll of Schlumberger developed the induction log from research he

had performed to create the mine detector during World War Two. He

was also responsible for the invention of the microlog, laterolog,

and microlaterolog. Henry

Doll of Schlumberger developed the induction log from research he

had performed to create the mine detector during World War Two. He

was also responsible for the invention of the microlog, laterolog,

and microlaterolog.

Analysis

of water saturation became more reliable because of reduced borehole

effect on the resistivity measurements, compared to conventional

electrical resistivity logs. To some degree, bed boundary effects

were more predictable and compensated for electronically. The

induction log has evolved considerably over its fifty year life

and is the most common log run today.

Comparison of Electrical Survey (ES) and Induction

Log (IL)

The

electrical, SP, and gamma ray logs all measured the average value

of rock properties over eighteen inches to five feet of rock thickness.

Beds thinner than this could not be detected or evaluated. The

microlog was introduced in 1948 and allowed resistivity in beds

as thin as two or three inches to be measured at a correspondingly

shallow depth of investigation into the rock. The log can be

thought of as a miniature ES log supported on a rubber pad

pressed tightly to the borehole wall.

The

curve shape approach to analysis was commonly used for microlog

data, although laboratory derived charts allowed quantitative

analysis of formation factor, and as a result, porosity.

The curve shape analysis for micrologs provided rapid visual identification

of zones which were invaded by drilling fluid, and were thus permeable

to some small degree. The log is still used today for this purpose.

Microlog circa

1949. Shaded areas show good SP and "positive separation",

indicating permeable rock. Combined with high resistivity on the ES

log, this combination of logs could pinpoint oil or gas reservoirs.

The

laterolog was also introduced in 1948 - 1949. It was a multi-electrode

electrical log designed to minimize borehole effects in salty

drilling mud. Again, improved resistivity values led to better

water saturation and porosity determinations, still using the

Archie method.

The

microlaterolog, to replace the microlog in salt mud, was first

seen in 1952. Curve-shape analysis was not easy, but standard

Archie methods worked well with this data. Other similar tools,

such as the proximity log, and the micro-spherically focused log,

are variations of the microlaterolog designed to improve shallow

resistivity measurements in a variety of borehole conditions.

Neutron

logs first appeared in 1938, but were not common until l946, when

better sources of neutron radiation became more readily available.

Neutrons emitted by the source, are absorbed by hydrogen atoms,

which are common in water and petroleum. Qualitative analysis

of porosity (which contains water or oil) was possible by detecting

the number of neutrons which were not absorbed but were scattered

back to the detector. In some tools, the captured gamma rays created

by the neutron bombardment were counted instead of the neutrons.

This

was the first independent source of porosity information that

did not rely on Archie's formation factor concept and the resistivity

log data. The tool had, and has, its faults, but modern neutron

logs are useful quantitative analysis aids. Again, better

detectors have increased the resolution and accuracy of the measurements.

The modern version of the neutron log compensates for borehole

size and a number of environment factors automatically.

The

two-receiver acoustic travel time (sonic) log showed up in 1957.

Laboratory work had demonstrated that the travel time of sound

in a rock, after adjustments for fluid and matrix rock travel

time values, was capable of estimating porosity. Thus, another

independent source of porosity data was born.

M.

J. Wyllie published an analysis method for apparent porosity

from the sonic log using the time average equation in 1956. It

is one of the most common analysis methods in use. The laboratory

work and relationships between porosity and sound velocity (or

travel time) was exhaustively studied between 1940 and 1965. Much

of the work was aimed at solving problems in seismic survey

analysis.

Strangely enough, the Wyllie formula, for all its success over

almost fifty years of use in log analysis, can be shown

to be physically incorrect in the laboratory and in theory for

many situations, especially those involving compressible fluids

such as gas.

The

sonic-resistivity crossplot was invented shortly after the sonic

log. It allowed visual as well as quantitative presentation of

porosity and water saturation results on one piece of paper without

the use of additional charts, nomographs, or slide rules (hand

calculators had not yet been invented). It was tedious work, but

thousands of crossplots were made during the sixties, and a few

less progressive analysts still use them today.

Sonic-Resistivity Crossplot Analysis for Porosity

and Water Saturation

Quick

look methods to differentiate hydrocarbon zones from water zones

also followed the introduction of the sonic log. One such technique,

the "Rwa Method", is still very popular. The principle

used was to quickly calculate, from the Archie water saturation

equation and the sonic log porosity value, the apparent water

resistivity which would make the zone 100% water saturated.

If

a particular value of water resistivity was considerably higher

than the trend of many other values from above and below it in

the borehole, then hydrocarbon could be suspected in the anomalous

zone. No shale corrections were made, so shaly sands often showed

poorly in this analysis.

Another

quick look method is called the overlay method. The simplest approach

was to overlay the resistivity log and the sonic log in such a

way as to have the two curves fall on top of each other in the

obvious water zones. Zones in which the resistivity log fell to

the right of the sonic log were either potential pay zones or

tight (non porous).

The

overlay method was improved by generating compatible scale logs

so that scaling differences did not cause false shows. The compatibility

could be created by transforming the resistivity and sonic curves

to apparent porosity or to apparent formation factor. This was

done at the wellsite by appropriate function formers in the surface

electronics, or back in the office by use of computer processing.

The

invention of the logarithmic presentation for resistivity data,

when the dual induction log was introduced in 1962, made quick

look overlay methods even more popular and practical at the well

site.

Many

modern logs are designed to give good visual impressions of lithology,

porosity, or hydrocarbon by means of compatible scale overlays.

The density-neutron combination log is the most common example.

The latest versions of computerized logging trucks even shade-in

the separation between compatible scaled logs to emphasize the

apparent prospective zones.

The

density log was introduced in l959. It was another independent

source of porosity data. With three sources of apparent porosity,

(sonic, neutron and density), in addition to the resistivity methods,

it was now possible to account for more variables. This led to

crossplot or chartbook methods which compared the apparent porosity

values from two sources, to help identify lithology (shale content

or limestone - dolomite ratio, for example). The

density log was introduced in l959. It was another independent

source of porosity data. With three sources of apparent porosity,

(sonic, neutron and density), in addition to the resistivity methods,

it was now possible to account for more variables. This led to

crossplot or chartbook methods which compared the apparent porosity

values from two sources, to help identify lithology (shale content

or limestone - dolomite ratio, for example).

The

sonic-density crossplot was common in the early sixties, with

the density-neutron crossplot becoming more common in the late

sixties, as the neutron logs became better calibrated and scaled

in porosity units. The

sonic-density crossplot was common in the early sixties, with

the density-neutron crossplot becoming more common in the late

sixties, as the neutron logs became better calibrated and scaled

in porosity units.

Since

a crossplot is merely the solution to three simultaneous equations

in three unknowns, the use of computers to solve these equations

was a popular subject in the early sixties. Extensions of this

concept to four, five or six simultaneous equations demanded a

computer since graphical methods could not cope with the multi-dimensional

aspect of the job.

<==

Early Computed Log c. 1966

The desired results from such methods are porosity and the percent

of each matrix rock type present. Usually one extra component

can be found for each additional independent logging tool measurement

used in the simultaneous equations. The method suffered if the

list of unknowns in the equations did not match the real rock

sequence. This can be mitigated, at least in part, by allowing

the computer program to search for the best lithologic model.

Linear

programming (simultaneous equations with constraints) was tried.

It was not very successful, because knowledge of rock properties,

the so-called known data, was not really very well known. As well,

tool response to rock mixtures was not well defined.

The

late fifties and early sixties also saw a great deal of work in

atomic physics and both the pulsed neutron (or atomic activation)

log and natural gamma ray spectroscopy log were described. However,

suitable tools did not become available until 1968, and were not

common until 1971.

The

pulsed neutron log provides another apparent porosity evaluation,

as well as an independent assessment of water saturation. The

logs are also called thermal decay time logs, chlorine logs, carbon/oxygen

logs or spectral gamma ray logs (note the lack of the word "natural"

in this case) depending on the details of the source-detector

systems and the rock properties derived from the data. They are

usually run in cased holes.

The

natural gamma ray spectrolog allows analysis of uranium,

thorium and potassium content in a formation. This is used to

help segregate shale from other naturally radioactive rocks, such

as uranium bearing dolomites or potassium rich sandstones. In

conjunction with other log data, it can help define the types

of clay minerals present in the shales.

The

nuclear-magnetic resonance log was described in 1956. The theory

suggested that effective porosity and permeability could be determined

from the measurements. Good examples of this are still rare even

after nearly fifty years of refinement- but Year 20XX versions

of the tools will probably succeed. Unfortunately, the tool sees

a very small fraction of the rock seen by other logs, so it may

never be realistic to compare values from such dissimilar rock

volumes.

Other

methods for interpreting permeability, based on empirical relationships

between porosity and water saturation had been presented prior

to l960 and are still used today. Some examples are the Timur,

Wyllie-Rose, and Coates-Dumanoir methods.

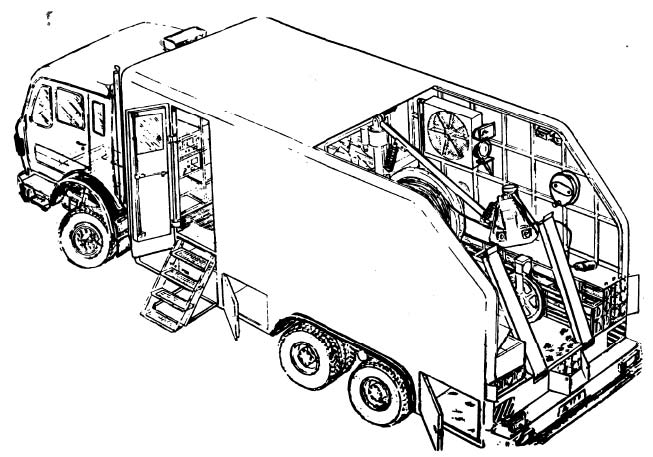

Sketxh of a logging truck circa 1962,

the year the author began his career in the industry

Prediction

of abnormal pressured zones, and potential drilling or blowout

problems, were developed from the various porosity estimating

logs, beginning in l956. This was based on depth-trend line analysis

of the sonic log primarily, although most logs, including density,

neutron, and resistivity logs can be used.

The

log types and analysis methods discussed so far are all

used in open-hole conditions, that is, after the well is drilled

but before it is cased with pipe and cement, and finally completed

to flow oil or gas (or heaven forbid, water). All the radioactive

logs (gamma ray, spectral gamma ray, neutron, pulsed neutron)

except density logs can be run in cased holes, and interpreted

with approximate corrections for casing size and thickness.

Resistivity

and older style sonic logs cannot be run in casing to obtain information

about the rocks, although the sonic log is used to evaluate the

cement behind the casing. Sonic wavetrain logs run through the

casing are sometimes useful in evaluation of the rocks, but are

most frequently used for cement evaluation. Recent versions of

sonic logs use computer processing of the wavetrains to determine

compressional, shear, and Stoneley wave travel times in both open

and cased-hole situations. Resistivity logging through casing

is also being developed.

Other

logs, such as temperature, flow-meter (spinner surveys), gradiomonometer

(a fancy name for fluid density meter), and noise logs are used

to assist in analysis of the location, amount, and type

of fluid flow in producing or injecting wells. The tools and techniques

have evolved gradually since l952, when the first serious effort

was made to evaluate well performance with logging tools.

While the early years were clearly a period of invention of

hardware and techniques, the middle years could be termed the

period of understanding. Although significant new tools were

developed, such as the sonic and density logs, the

analysis process required more formidable effort.

Customers wanted more reliable answers along with the more

reliable logging tools.

|