|

Identifying Fluid Contacts

Identifying Fluid Contacts

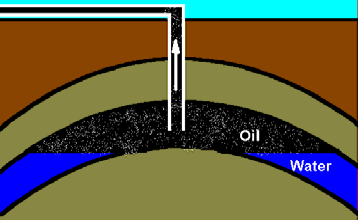

Gravity segregation of fluids puts gas on top of oil (or water)

and oil on top of water in most reservoirs. The gas/oil or gas/water

contact is fairly sharp. The oil/water contact is usually gradational,

covering a few to many feet. The top of the transition zone is

the base of clean oil production. The base of the transition zone

is the top of free water. The length of the transition zone depends

on the permeability of the rock - lower permeability gives longer

transition zones.

Contacts in aquifer drive: Gas / Oil /

Water. Initial conditions (left)

and after some production (right) - Oil / Water contact rises.

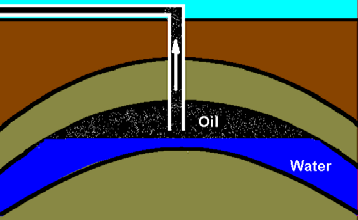

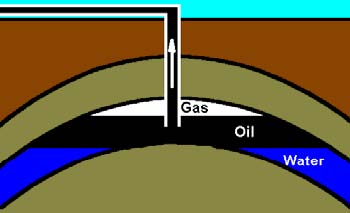

Contacts

in gas expansion drive: Oil / Water. Initial conditions. After

some production Gas / Oil contact drops. Contacts

in gas expansion drive: Oil / Water. Initial conditions. After

some production Gas / Oil contact drops.

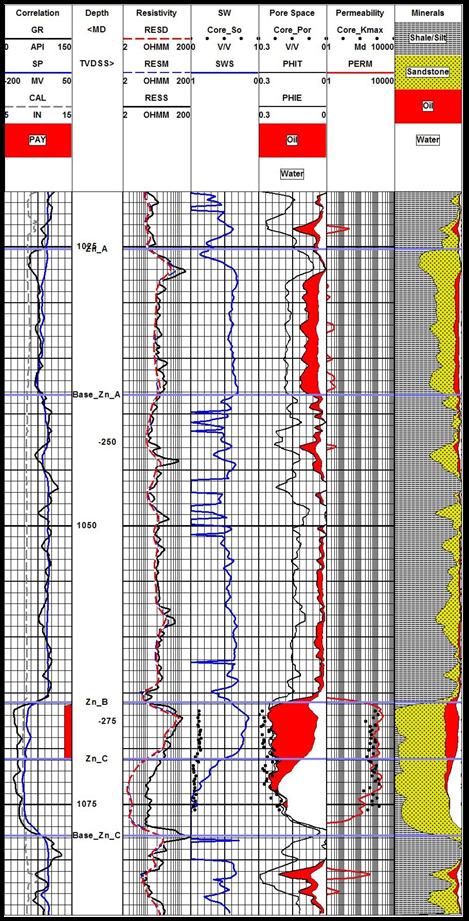

Oil water contact on depth plot (just above 1070 meters)

In

some wells, a tar mat exists just above the original oil/water

contact. There is little moveable oil in the tar mat. During production,

aquifer influx or water flooding can position water above the

tar mat, giving rise to an oil/water/tar mat/water profile.

In

tar sands, it is possible to have gas over water over oil, because

the oil is heavier than the water.

A

transition zone normally shows an increase in water saturation

and bulk volume water as depth increases, culminating in 100%

water saturation. An example from a Glauconitic Sandstone from

Alberta is shown at the left.

A

particular well may not penetrate the water zone due to the structure

of the trap. Some reservoirs have no water leg and thus no transition

zone and no water contact.

Infill

wells drilled into older reservoirs may encounter secondary gas

caps, deeper gas caps, or shallower water contacts that were not

present when the reservoir was discovered. Both current and original

contacts may be visible on logs, but differences between their

signatures may be very subtle. For example, a secondary gas cap

may contain immobile oil, reducing the amount of gas crossover.

Zones swept by aquifer influx will contain residual oil, so water

saturation will not be 100%. Zones swept by a waterflood are especially

difficult to detect because the injected water may be much more

resistive than the original formation water.

Running

and analyzing TDT or pulsed neutron logs to find water contact

changes over time is called reservoir monitoring. By combining

dated water contacts from both cased hole and open hole logs,

a clearer picture of reservoir performance can be obtained.

PORE GEOMETRY ISSUES

PORE GEOMETRY ISSUES

Identification

of transition zones is sometimes confused by changes in pore geometry

that give increasing water saturation with depth. Sands with increasing shaliness with depth also look like transition zones. There are

often differences of opinion as to whether the zone is getting

wetter because it is approaching a water contact or instead is

merely becoming wetter due to lower quality rock.

In

such cases, top of transition zone must be determined by drill

stem or production tests. Saturation cutoffs must be adjusted

to agree with test results. The example shown below show two interpretations of the transition zone in a

complex reservoir. The producing interval is shown by the narrow

black bar near the bottom of the porous interval. Since water

cut is less than 6%, the second interpretation is the

correct one; the first interpretation would suggest a

much higher water cut from this perforated interval.

First interpretation shows long apparent transition zone. Perfs in this interval produce clean oil so

this cannot be a real

transition zone

Second interpretation with short transition zone adjusted

to agree with production data.

The

steps shown in the saturation curve represent pore geometry changes

caused by progressively increasing isolated vugs deeper in the

reservoir. The porosity times water saturation product defines

different "rock types' or pore geometry facies. These are

shown best in a porosity vs water saturation crossplot with different

colours indicate the different facies.

Porosity vs Water Saturation crossplot showing

different rock types tracing different hyperbolic trends.

RULES FOR PICKing Fluid Contacts

RULES FOR PICKing Fluid Contacts

Fluid

contacts can be picked using the following rules:

1.

Gas/oil or gas/water contacts are picked at the point below which

gas crossover on the shale and matrix corrected density neutron

log disappears. Perforations just below this depth will produce

gas with water or gas with oil. Perforations above this depth

should produce mostly gas. Gas crossover on recorded logs can

be masked by shale or heavy mineral effects. The best way to look

for crossover in these cases is to create shale corrected logs,

rescaled for the density of the minerals in the zones and display

these curves on depth plots. In gas filled dolomite reservoirs,

this is the only way to see the gas crossover - such log displays

can be made in the field on the logging truck if you suspect gas

and dolomite might be present.

2.

Oil/water contact is at the depth where water saturation first

reaches (close to) 100%. This sometimes called the free water

level (FWL). Perforations below this point will produce 100% water.

This can usually be picked on the resistivity log where resistivity

reaches its lowest values in a clean, porous reservoir. Shaliness,

varying porosity, and residual oil, or bitumen may mask this pick.

A clearly defined contact in one well may be located in a shale

in an offset well.

3.

Top of transition zone is picked at the depth above which the

bulk volume water (and usually water saturation) becomes nearly

constant or reaches its minimum value. Perforations below this

point will produce oil with some water or 100% water if oil viscosity

is high. Water saturation in this zone may still be quite low

and may pass cutoffs. Since some of the oil in the transition

zone may be pushed upward by an active aquifer, some operators

count all this oil in their reservoir volume. Others count only

down to an arbitrary water saturation (say 50%) while others stop

counting at the top of transition or even higher. Water saturation

in the transition zone is above irreducible water saturation,

which is usually demonstrated by the production characteristics

or drill stem tests on these intervals. CAUTION: Top of transition

may be masked by changes in pore geometry or shaliness, as shown

in the example given above.

Perforating

too close to a gas/oil or oil/water contact will cause problems.

The drawdown pressure caused by production will allow gas to flow

down into perfs near the gas. Similarly, water can be drawn up

to co-mingle with oil production. Problems can be especially severe

in fractured reservoirs, and can be disastrous if management is

greedy or stupid about desired flow rates.

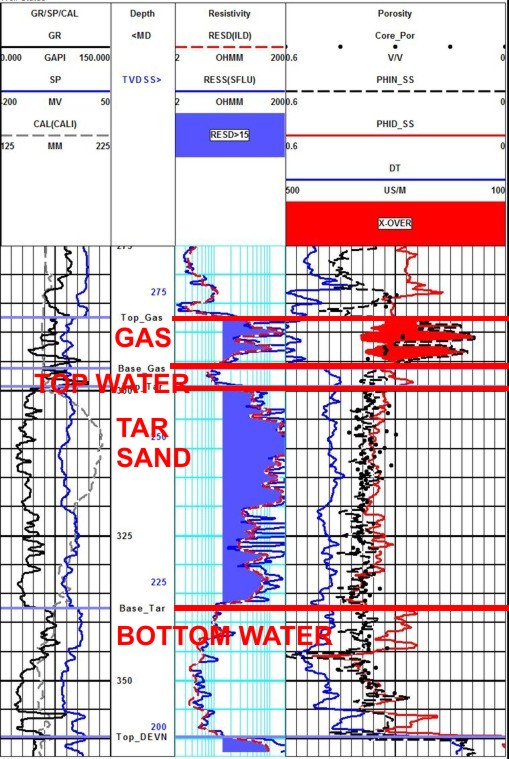

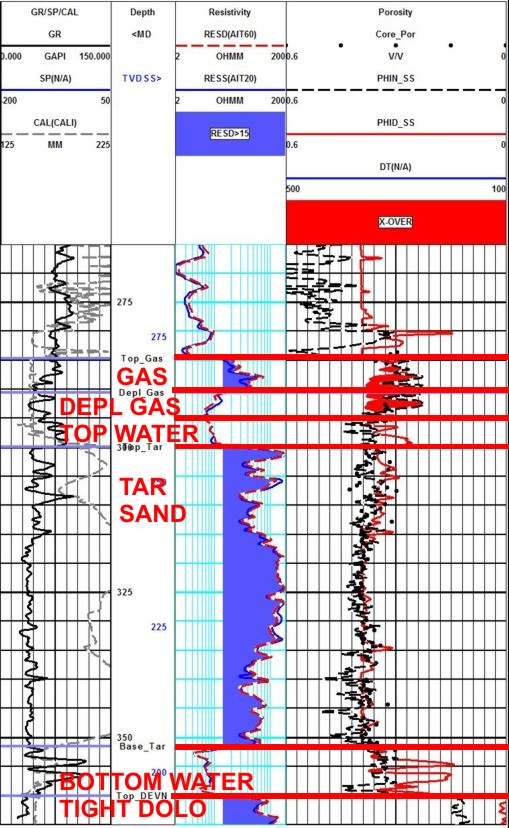

GAS / WATER -- GAS / DEPLETED GAS / WATER EXAMPLES

GAS / WATER -- GAS / DEPLETED GAS / WATER EXAMPLES

In

the example below, two wells are shown that are less than 100

meters apart. The wells are drilled for the bitumen sand but gas

and water may sit directly above the oil sand. The depth plots

are composite plots with GR and caliper in Track 1, resistivity

in Track 2 and density, neutron, and core porosity in Track 3 ad

4. THe vertical scale is highly compressed -- the grid lines are

5 meters apart.

Oil sand (both wells) with gas above water (top left) and partially

depleted gas (above right).

The older well (left) shows gas

crossover (shaded red) and moderate resistivity (shaded blue above

20 ohm-m) over 15+ meters of gas pay. Below is a water sand (low

resistivity and no crossover). Below that is the oil sand (high

resistivity, shaded blue). The gas-water contact is confirmed by the

base of the high resistivity and by the base of the crossover. If no

water zone was present, only base of crossover would indicate the

contact. Gas production was begun immediately upon well

completion.

Contrast this with the well on

the right, drilled 5 years later, but less than 100 meters away.

There is still crossover on the entire gas interval, but the high

resistivity covers only the top half of the zone. The lower half of

the gas zone now has low resistivity - it is wetter than before,

indicating that some of the gas has gone. Production from other

wells has partially depleted this reservoir. Crossover still exists

in the depleted zone because of residual gas.

In fact, residual gas

in a depleted zone is about the same as residual gas in an invaded

zone, so unless recovery factor is extremely high, depleted gas

zones may have some crossover, if they are clean enough to show

crossover at all. The gas-water contact is at the base of the high

resistivity and the base of the original gas zone is at the base of

gas crossover. There can be mid-zone gas in the bitumen interval as

well so keep your eyes open for the unexpected.

The water between the gas and oil

is called "top water" by the oil explorationist, to distinguish it

from the "bottom water" below the oil. Either or both of the gas and

top water zones may be missing in this region.

The moral of the tale is that gas

crossover can be misleading. First, prove it is gas and not bad hole

condition or sandstone on a limestone scale. Second, check that the

zone is resistive enough to still have a reasonably attractive water

saturation. Then test the zone to be sure.

|