|

CaRBON DIOXIDE BASICS

CaRBON DIOXIDE BASICS

Selection, evaluation, and monitoring carbon dioxide storage

reservoirs is a multi-disciplined task, in which petrophysics plays

a vital role. Most of the discussion about CO2 also applies to

natural gas (CH4) and hydrogen (H2) storage reservoirs. This article

describes the special properties of CO2, storage reservoir criteria,

the role of petrophysics, followed by visual and quantitative log

analysis methods, and an example from a CO2 monitoring project using

the fast neutron cross section measurement.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a chemical compound occurring as a colorless

non-combustible gas with a density about 153% of that of dry air. It

has a sharp and acidic odour and taste at high concentrations (eg

carbonated water), but at atmospheric concentrations it is odourless

and tasteless. Because CO2 is heavier than air, it can collect in

low or enclosed spaces, asphyxiating occupants due to lack of

oxygen.

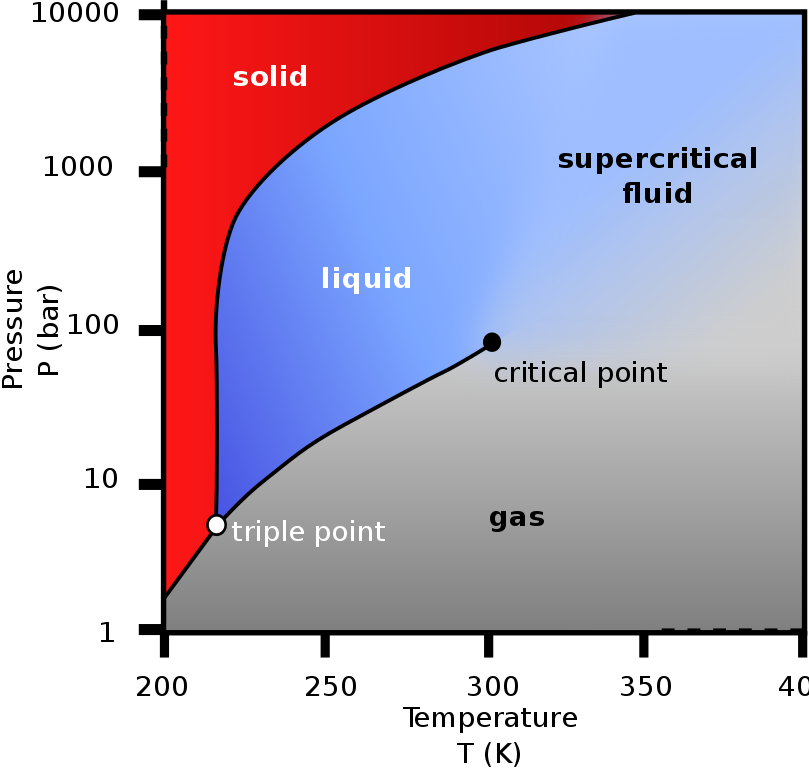

CO2 has no liquid phase at pressures below 518 kPa. At 101 kPa, the

gas deposits directly to a solid (dry ice) at temperatures below

−78.5°C; the solid sublimes to gas above this temperature. Liquid

CO2 forms only at pressures above 518 kPa. The density of dry ice

increases with decreasing temperature and ranges between 1550 and

1700 kg/m3 below −78 °C.

Most elements and simple compounds can exist in

the gas, liquid or solid phase depending on temperature and

pressure. A few can exist in a fourth phase, as a supercritical

fluid when above a critical temperature and pressure. The critical

point for CO2 is 31.1 C and 7.38 MPa, above which the distinction

between the gas and liquid phase disappears, entering the

supercritical fluid phase. A supercritical fluid behaves like a gas,

moving easily through porous media, but has densities more like

liquids. Density of supercritical CO2 is 600 to 800 kg/m3.

Geological CO2 storage makes use of these special supercritical

properties, allowing for efficient transportation and injection of

CO2 into underground reservoirs.

Phase diagram of carbon dioxide (Wikipedia)

SOURCES AND

USES OF CARBON DIOXIDE

SOURCES AND

USES OF CARBON DIOXIDE

Carbon dioxide occurs naturally in our atmosphere in trace

amounts, about 412 ppm by volume, compared to pre-industrial

levels of 280 ppm. CO2 is one of several green house gases

(GHGs) that are implicated in global warming and climate

change. Reducing CO2 emissions and CO2 capture and storage

(CCS) to mitigate these issues are goals of industry and

government.

Natural sources of CO2 include volcanoes, forest fires, hot

springs, geysers, dissolution of carbonate rocks, and decay

of organic matter, including landfills and backyard compost.

It is soluble in water and occurs naturally in groundwater

and all surface water bodies.

Human sources include combustion of wood, peat and other

organic fuels, fossil fuels, and unwanted by-product of many

industrial processes, such as manufacture of cement, steel,

and plastics. Agriculture and food processing is a large CO2

emitter, mostly unrecognized because it is so dispersed

across the planet.

Major uses of carbon dioxide are as a feedstock for

synthetic fuels and other chemicals. It is used in welding,

fire extinguishers, pressurizing agents, enhanced oil

recovery (EOR), and as a solvent. It is the key ingredient

in carbonated drinks. The solid form (dry ice) is used as a

refrigerant and as an abrasive in a much less messy form of

sand-blasting.

Carbon dioxide is essential for all plant life, which

generates the oxygen essential for human existence. However,

too much of a good thing is turning into a bad thing, so we

must learn to reduce emissions and to store what we can’t

reduce in a safe place, instead of into the atmosphere.

CARBON STORAGE

IN GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS

CARBON STORAGE

IN GEOLOGICAL FORMATIONS

Geological sequestration refers to the storage of CO2

underground in depleted oil and gas reservoirs, saline-water bearing

formations, or deep, un-minable coal beds. The storage capacity of

these reservoirs worldwide is enormous, estimated as large as 20,000

Giga tonnes of CO2.

As CO2 is captured from an industrial source, such as a cement

plant, steel mill, or oil refinery, it is compressed to about 10 MPa

so that it becomes a supercritical fluid. In this form, the CO2 is

easy to transport via pipeline to the storage location. The CO2 is

then injected into an underground porous reservoir, where it will

remain as a stable supercritical fluid.

At these storage conditions, the density of

supercritical CO2 is 600 to 800 kg/m3, lighter than water, so it

will rise to the top of the reservoir and be trapped by the caprock

above the reservoir. As more CO2 is injected, it will spread

laterally until the reservoir has been filled to its capacity.

A good reservoir for carbon dioxide storage is one with medium to

high porosity and permeability, with no faults or fractures, and a

well defined structural or stratigraphic trap. The seal or caprock

is usually a thick shale, an evaporite such as halite or anhydrite,

or a subsurface lava flow like basalt. A good reservoir for carbon dioxide storage is one with medium to

high porosity and permeability, with no faults or fractures, and a

well defined structural or stratigraphic trap. The seal or caprock

is usually a thick shale, an evaporite such as halite or anhydrite,

or a subsurface lava flow like basalt.

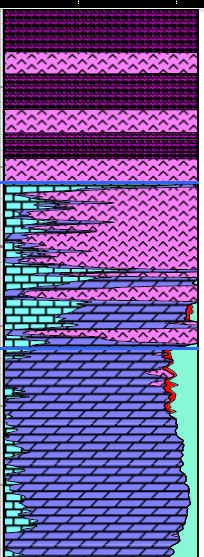

Porosity-lithology depth plot

showing evaporite caprock and porous carbonate suitable for a CO2

storage reservoir

If there are faults or fractures, there is a

strong possibility that the CO2 could migrate to other reservoirs,

causing economic loss to others, or a leak to the surface, which

could be dangerous to life in the surrounding area.

The dominant monitoring technique to date is

time-lapse 3-D seismic imaging to locate the CO2 plume in the

reservoir. Well logs run periodically in monitoring wells are also

widely used.

PETROPHYSICS FOR

CARBON STORAGE PROJECTSfs

PETROPHYSICS FOR

CARBON STORAGE PROJECTSfs

Petrophysics has a large role to play in the green

economy. Hundreds of thousands of legacy wells have been

drilled in the past, in search of fossil fuels. These wells

penetrate reservoirs which may find new life by defining

potential storage for carbon capture and storage (CCS). The

competent petrophysicist can analyze these old wells with

key suitability criteria in mind, to validate mechanical

earth models (MEM), which tend to be more heavily weighted

towards seismic inputs. Seisic can give a good overview of

the reservoir, but only petrpphysics can fill in the details

that can determine success or failure of the project.

Identifying a container for CO2 is the most

important step in the process; a suitable site ensures the injected

CO2 will stay where it is supposed to be for the foreseeable future.

The key criteria for which petrophysical

analysis can provide ground truth for the reservoir model are: shale

characterization, porosity, permeability, mobility and

saturations. Including legacy wells means better definition of the

areal extent of the potential container. Once the container has been

selected and the most porous snf permeable zones selected for

injection well locations, the petrophysicist will run logs to

evaluate the well for fractures and casing / cement integrity. In

the final phase, the petrophysicist will evaluate the monitor wells

to assess how well the CO2 has entered the pore space.

Due to the risk to life from a CO2 leak to

surface, there is no room for amatuers or novices in this work.

Expert petrophysical advice should be sought and be acted upon at

every stage in the project development and operation.

Here are the stages in the development of a

carbon storage reservoir that require competent petrophysical

analysis, coupled with other geoscience and reservoir engineering

work.

PHASE 1: Find a Suitable Storage

Reservoir

Criteria: thick competent caprock, no faults or fractures, no

barriers to vertical flow (shale or anhydrite interbeds), thick

porous and permeable reservoir (saline water bearing or depleted oil

or gas zone), structural or stratigraphic trap (area, volume, spill

point), economics, proximity to CO2 source.

Action Items: prepare complete reservoir study, integrating

geological, geophysical, and petrophysical analysis (with mechanical

properties calculations) on all available wells (including entire

caprock sequence), prepare structural maps and cross sections, pore

volume calculations, depth-pressure-temperature profiles.

PHASE 2: Locate and Evaluate Injection Well(s)

Action Items: select injection well location(s) based on reservoir

model, drill through best porosity to optimize CO2 injection rate,

run and analyze full log suite, run resistivity image log to find

unexpected fractures, run ultra- sonic cement integrity log to find

leaks or channels, repair as needed. Run Pulsar (induced gamma ray

spectroscopy with fast neutron cross section) for comparison to same

log in monitor wells.

PHASE 3: Run Baseline Well Logs In Monitor Wells

Action Items: In open hole run resistivity image log to find

unexpected fractures. In cased hole, run ultra- sonic cement

integrity log to find leaks, repair as needed. Before CO2 injection

begins, run baseline logs over storage reservoir, entire caprock,

and 1000 meters above caprock.

Option 1: Pulsar log, generically known as the advanced pulsed

neutron log, which includes gamma ray (GR), neutron porosity (TPHI),

capture cross section (SIGMA), and fast neutron cross section

(FNXS). Best for quantitative CO2 analysis. Also capable of

elemental capture and inelastic

spectroscopy for matrix rock and fluid identification.

Option 2: Standard pulsed neutron (TDT) log which includes gamma

ray, neutron porosity, capture cross section.

Option 3: Gamma ray, shear and compressional sonic, neutron

porosity, cased hole density**, cased hole resistivity** (** =

optional but desirable)

PHASE 4: Run Time Lapse Logs to Monitor CO2 Plume Development

Action Items: run same logs as Stage 3, use visual analysis rules in

text below to determine if CO2 has reached this monitor well. Run

monitor logs over same interval as baseline logs. Look for evidence

of leaks through and above caprock.

VISUAL LOG

ANALYSIS RULES FOR CO2

VISUAL LOG

ANALYSIS RULES FOR CO2

If CO2 is present at a monitor well,

then the time-lapse log data in the CO2 plume will be different than

the baseline log, in which no CO2 was present.

These rules are based on the log response to CO2 compared to

water-filled porosity, highlighted in Table 1.

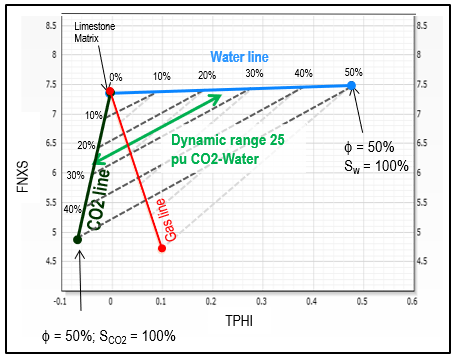

For Pulsar log:

gamma ray (GR) will be unchanged from baseline values

neutron porosity from Pulsar (TPHI) will be much lower or

negative

capture cross section (SIGMA) will be much lower

fast neutron cross section (FNXS) will be lower

See graph below to estimate

approximate CO2 saturation using TPHI and FNXS. FNXS is a

measurement independent of hydrogen index which primarily responds

to the atomic density of the formation; it provided an additional

method for CO2 detection and quantification, and it enables solving

for more complex scenarios when integrated to other rock properties,

such as neutron porosity.

For pulsed neutron (TDT) logs:

gamma ray (GR) will be unchanged from baseline values

neutron porosity from TDT (TPHI) will be much lower or negative

capture cross section (SIGMA) will be much lower

The following rules are for conventional logs run through casing:

gamma ray (GR) will be unchanged from baseline values

shear sonic (DTS) will be unchanged

compressional sonic (DTC) will be higher

resistivity (RESD) will be higher

density (DENS) will be lower (density porosity (PHID) will be

higher)

neutron porosity (PHIN) will be much lower or negative

TPHI vs FNXS crossplot for estimating carbon dioxide

saturation Sco2

QUANTITATIVE

METHODS FOR CO2 LOG ANALYSIS

QUANTITATIVE

METHODS FOR CO2 LOG ANALYSIS

Quantitative analysis of carbon

dioxide saturation (Sco2) is possible using capture cross section

(SIGMA), neutron porosity (TPHI), or fast neutron cross section

(FNXS) using the classic log response equation by substituting CO2

parameters for the hydrocarbon terms. CO2 has zero hydrogen index so

TPHI reads total porosity only if the zone is 100% wet. For a zone

filled with super-critical CO2, TPHI will read near zero porosity.

SIGMA and FNXS also have very different properties for CO2 compared

to those for water, so all three terms can be used as CO2 saturation

indicators. See Table 1.

Here is the log response equation for the SIGMA measurement with

only CO2 and water in the porosity:

1: SIGMA = PHIe * Sw * SIGw (water term)

+ PHIe * (1 - Sw) * SIGco2 (carbon dioxide term)

+ Vsh * SIGsh (shale term)

+ (1 - Vsh - PHIe) * Sum (Vi * SIGi) (matrix

term)

Where:

SIGco2 = log reading in 100% carbon dioxide

SIGi = log reading in 100% of the ith component of matrix rock

SIGMA = log reading

SIGsh = log reading in 100% shale

SIGw = log reading in 100% water

PHIe = effective porosity (fractional)

Sco2 = carbon dioxide saturation in reservoir (fractional)

Sw = water saturation in reservoir (fractional)

Vi = volume of ith component of matrix rock

Vsh = volume of shale (fractional)

WS(ppm) = water salinity NaCl

equivalent (parts per million)

This equation is solved for Sw by assuming all other variables are

known or previously calculated:

2: SIGw = 22.0 + 0.000404 * WS(ppm)

3: SIGm = Sum (Vi * SIGi)

4: PHIe = TPHI from baseline log before CO2 injection, OR from

open hole logs

5: SWtdt = ((SIGMA - SIGm) - PHIe * (SIGco2 – SIGm) - Vsh * (SIGsh

- SIGm))

/ (PHIe * (SIGw - SIGco2))

6: Sco2 = 1 - SWtdt

Similarly for FNXS:

7: FNXSm = Sum (Vi * FNXSi)

/ (PHIe * (FNXSw - FNXSco2))

8: SWfnxs = ((FNXS-FNXSm)-PHIe*(FNXSco2-FNXSm)-Vsh*(FNXSsh-FNXSm))

/ (PHIe * (FNXSw - FNXSco2))

9: Sco2 = 1 - SWfnxs

And for TPHI:

10: TPHIm = Sum (Vi * TPHIi)

11: SWtphi = ((TPHI-TPHIm)-PHIe*(TPHIco2-TPHIm)-Vsh*(TPHIsh-TPHIm))

/ (PHIe * (TPHIw - TPHIco2))

12: Sco2 = 1 – SWtphi

The FNXS model has the best resolution for CO2 monitoring. FNXS

values for helium and nitrogen are reported to be similar to CO2 so

the Pulsar log can be used to evaluate helium wells through casing.

Other uses include monitoring natural gas and hydrogen storage

reservoirs.

CO2 LOG ANALYSIS

EXAMPLE

CO2 LOG ANALYSIS

EXAMPLE

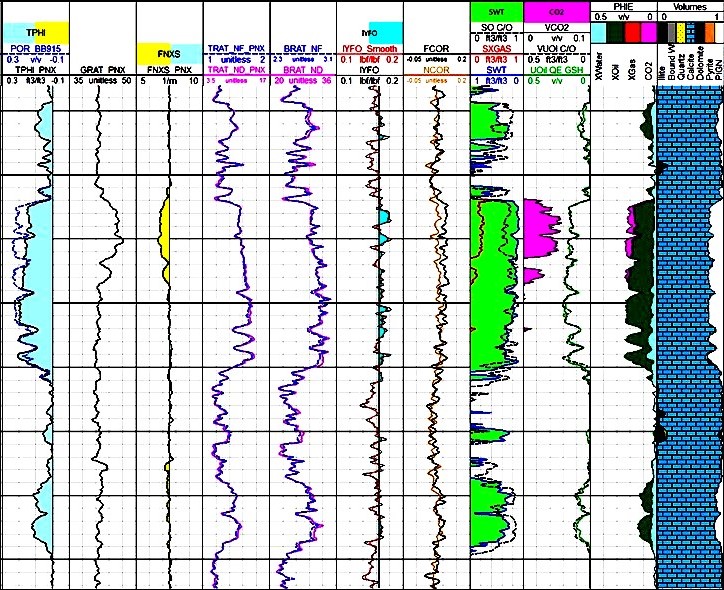

Examples of CO2 detection and quantification at current

reservoir condition. Different gas indicators are presented,

including Sigma, Neutron count rates and porosity, Fast

Neutron Cross Section, and its deviation from Fast Neutron

Cross Section of matrix components in presence of gas.

SIGMA, TPHI, FNXS end points calculated based on gas density

and composition. Lithology and

porosity are measured based on induced gamma ray

spectroscopy combined to TPHI and FNXS, eliminating the need

for open hole logs.

TABLE 1:

NUCLEAR PROPERTIES FOR TDT ad PULSAR LOGS

TABLE 1:

NUCLEAR PROPERTIES FOR TDT ad PULSAR LOGS

Material Sigma

(c.u.) TPHI FNXS (1/m)

Quartz 4.55 –0.03 6.84

Calcite 7.08 0.00 7.51

Dolomite 4.70 0.03 8.51

Orthoclase 15.82 –0.05 6.33

Albite 7.65 –0.04 6.69

Anhydrite 12.45 –0.03 7.14

Pyrite 90.53 0.01 6.60

Bituminous Coal 15.79 0.68 7.72

Dry Illite 20.79a 0.22 8.06

Wet Illite 21.00 a 0.34 8.02

Dry Smectite 14.36 a 0.29 8.36

Wet Smectite 19.23 a 0.68 8.60

Kerogen (CH 1.3g/cc) 20.18 0.98 9.07

CH4 (0.05 g/cc) 2.50 –0.05 0.67

CH4 (0.15 g/cc) 7.50 0.21 2.01

CH4 (0.25 g/cc) 12.50 0.47 3.36

Oil (C3H8 0.5g/cc) 18.21 0.78 5.44

Oil (C3H8 0.6g/cc) 21.85 0.97 6.53

Diesel (CH1.8 0.89 g/cc) 23.30 1.08 7.98

CO2 (0.6 g/cc) 0.03 –0.12 2.24

Water 0 ppm 22.2 1.00 7.800

Water 200,000 ppm 97.2 0.90 7.36

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Chiara Cavalleri of Schlumberger for contributing content

for this article, including examples and Table 1. Thanks also

to Sandra Bleue for acting as research assistant on the Pulsar log

and the fast neutron cross section (FNXS) measurement.

REFERENCE

Fast Neutron Cross-Section Measurement Physics and Applications

Tong Zhou, David Rose, et al

SPWLA 57th Annual Symposium, 25 – 29 June 2022

|