|

Deciding

What The Patterns Mean

Deciding

What The Patterns Mean

There are two basic ways to decide what red and blue patterns

mean from a structural point of view. The first is to sketch a

cross sectional view of the well bore with the bedding planes

positioned according to the dipmeter data. These can be made by

hand or with stick diagram software.

The

second is to use a catalog or cook book of typical patterns to

compare your pattern with those already described. As mentioned

earlier, regional dip removal can change a pattern, so the cook

book approach is not too useful unless dip removal has been done.

Also, the cook book patterns presume that dip directions shown

on logs are always parallel to your cross section direction. This

is not always true so it becomes necessary to rotate dips to get

the "best" patterns. Both transverse and longitudinal

cross sections should be visualized when analyzing dip patterns.

Before

you start sketching patterns, review the basic structural features

described earlier in this Chapter. Then draw a sketch of the dipmeter

data. Take a piece of graph paper or blank well log paper and

draw a vertical line to represent the wellbore. A log print with

gamma ray, SP, and resistivity is also a good place to draw your

diagram.

Select

the interval you wish to analyze and mark some depth lines to

orient your data. For structural analysis, a compressed scale

of 1 or 2 inches to 100 feet or smaller is appropriate. Transfer

the position of the black patterns to your sketch. These represent

breaks in the geologic sequence, such as unconformities or tops

and bottoms of sedimentary structures. Use the gamma ray curve

or a computed lithology log and the well history data as guides

to major erosional surfaces.

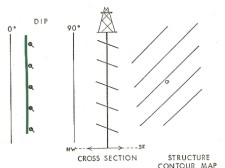

Stick plot of regional dip Stick plot of regional dip

Next,

choose regional dip in each major rock unit. At this point you

have to decide on the direction of cross section that your sketch

will represent. Usually, for structural analysis, it is chosen

to be the regional dip direction, although another sketch drawn

at right angles to the first may be useful in many cases.

For

example, if regional dip is to the south east, the cross section

should run from north west to south east. Draw short hash marks

on the well bore at an angle representing the actual dip shown

on the log. Some vertical exaggeration may be appropriate. An

example of this simple case is shown above.

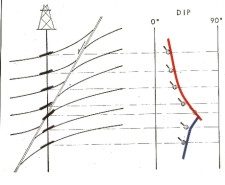

Stick diagram for a normal fault with drag Stick diagram for a normal fault with drag

Next,

position representative samples of the dip from the blue and red

patterns onto your sketch. You are really creating your own stick

plot. It may be helpful to include a sketch of the dipmeter log

itself on the same piece of paper. If

the red and blue patterns are contained within a sand body, they

are stratigraphic dips and should not be used in a structural

interpretation.

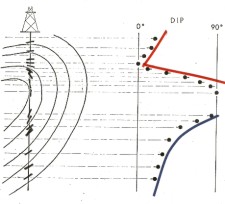

Stick diagram for an overturned anticline

Now

comes the hard part. Extend the hash marks to represent the bedding

planes of a structure. Basically you are only dealing with regional

dip, anticlines, synclines, unconformities, and faults. To propose

a fault, there should be some evidence from the well history,

some scattered dips at the break between the red and blue patterns,

a change in direction of dip, some missing or repeated section,

or drag and rollover features. The red pattern is usually connected

to the green pattern above it.

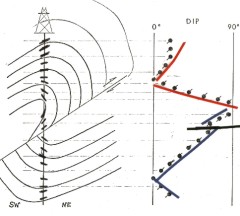

Stick diagram for overthrust fault Stick diagram for overthrust fault

Reverse

faults and overturned anticlines can have similar patterns - the

anticline is distinguished by dips approaching 90 degrees, whereas reverse faults seldom do this.

Overthrust faults will usually show an abrupt change in dip direction

near the fault plane

Normal

faults, overthrust faults, channels, unconformities, and disconformities

can have similar patterns - repeat section indicates the overthrust

case. The lithology and dips indicating crossbedding help distinguish

channels. Choose the model which suits the local geology the best.

Most patterns can be interpreted without imposing a fault and

the most common error in dipmeter analysis is the suggestion of

too many faults.

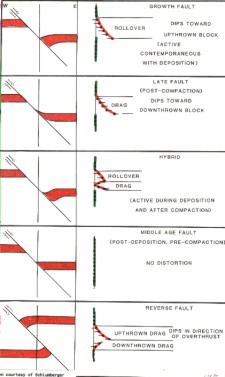

Normal faults (left, reverse fault (left bottom),

growth faults (right)

Growth

faults, contemporaneous with deposition, usually show rollover,

which is a dip pointing toward the upthrown block.

Post-depositional faults usually show drag, which is a dip

pointing toward the downthrown block. Hybrid faults can exhibit

complex patterns. Some faults show no rollover or drag. Remember

the effect of regional dip on these patterns.

Drawing

your own stick diagram and interpreting a plausible geologic section

to match it takes practice, patience, and a good grasp of 3-D

space. A good knowledge of geology doesn't hurt. The effect of

hole deviation must also be considered. Although the dips presented

on the log are true dips, with hole deviation taken into account,

their position in space may not have been corrected for true vertical

depth or the track of the borehole.

|