|

Choosing

and Using Regional Dip

Choosing

and Using Regional Dip

Regional dip, often called structural dip, is chosen in zones

where dip angle and direction are consistent, with a minimum of

scatter. These are GREEN patterns. Due to the

roughness of the borehole, and statistical variations in the correlation

measurements, even a zone with zero dip will show some scatter.

In particular, dip direction may appear to fluctuate wildly when

dip is near zero.

Regional

dip may not be easy to find. In thick sandstones, there may be

too many stratigraphic features, and in thick carbonates there

may be no bedding or too many fractures. Therefore, shale sections

should be preferred for the selection of structural dip. If there

is not much shale, choose the minimum consistent dips in the sands.

However,

shale sections do not always exhibit a regular dip. The mode of

deposition as well as post-depositional slumping or fracturing

may induce erratic dips. Bad or rough hole will also cause dips

in shale beds to be scattered. A statistical approach may then

be needed to determine structural dip, and local experience is

the best guide. Here is a case for using the modified Schmidt

plot or the frequency azimuth plot to help find regional dip.

It

is essential to subtract the structural dip (by means of dip vector

rotation), preferably by having a regional dip removed arrow plot

created in the computer. Indeed, a blue pattern may become a red

one and vice versa after subtraction of the general trend. The

term "absolute red" and "absolute blue" are

used to describe patterns which are distorted by regional dip.

If,

after drawing the patterns, you find regional dip to be greater

than about 4 degrees in any zone, you should have the log re-displayed

with dip removed. Obviously a different amount of dip will have

to be removed from different geologic sections. Pick these values

for each section from your green patterns between each major break

defined by the black patterns. If,

after drawing the patterns, you find regional dip to be greater

than about 4 degrees in any zone, you should have the log re-displayed

with dip removed. Obviously a different amount of dip will have

to be removed from different geologic sections. Pick these values

for each section from your green patterns between each major break

defined by the black patterns.

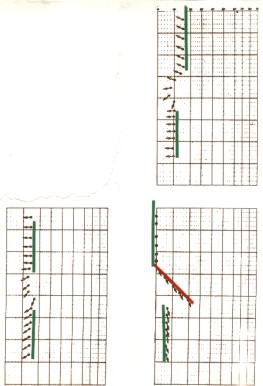

Effect of regional dip removal on pattern shape

The

illustration at the right shows three dipmeter presentations of the same structure.

Each has a different regional dip superimposed on the red pattern,

which is only visible in one of the illustrations. This emphasizes

the absolute necessity of working with dip removed data. You will

have to re-analyze the dip removed log for red and blue patterns.

You

will use these ONLY to identify the nature of the structural features

and the direction to thicker pay zones. The true dip and direction

of beds is still contained on the original log, and it is still

used for mapping structures and looking for the next drilling

location.

A

dipmeter log should always be correlated with the rest of the

open hole logs when the patterns are being drawn. A computed lithology

log is especially helpful to prevent drawing silly patterns which

cannot be supported by the obvious lithology. For instance, it

would make little sense to unite in the same blue pattern two

arrows belonging to different lithological units. A good well

history and the formation tops should also be at hand, since most

major unconformities will occur at one of these points.

Some

of the modern dipmeter presentations, such as SYNDIP, GEODIP.

and STRATIM will make life much easier. However, they are only

available on modern logs, and even then, may not have been run

(to save money), or may not be in the well file or in the public

domain. These logs are aids, not answers - be sure the aid is

properly processed and makes sense in light of other known data.

On older wells, you will have to create your own equivalent aids

by laying out and possibly analyzing the other open hole logs.

The minimum requirement is a gamma ray or SP log at the same depth

scale as the dipmeter arrow plot.

|