|

Analysis of Dipmeter Data

- StructurE

Analysis of Dipmeter Data

- StructurE

The traditional analysis of dipmeters makes use of patterns seen

on the arrow plot, augmented by those seen on azimuth frequency

plots.

An

overview of the thought processes were described by E. L. Bigelow

in "Making More Intelligent Use of Dipmeter Information",

published in The Log Analyst in five parts beginning January 1985.

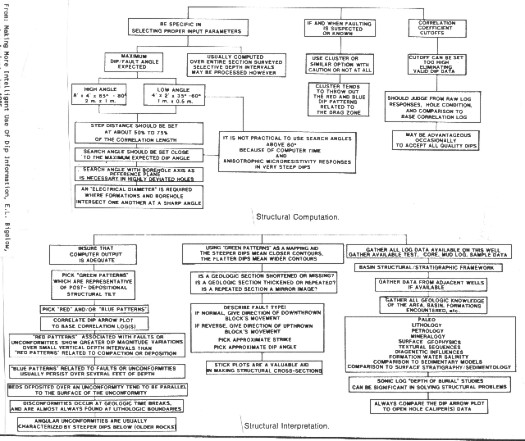

The flowchart below, taken from that paper, demonstrates the complexity

and interrelated nature of the data acquisition. processing, and

analysis problem. A review of Mr. Bigelow's paper will provide

many insights not covered in this Chapter, due to lack of space

Flow chart for dipmeter processing decisions

(upper), interpretation

(lower) for structural analysis

Structural

analysis begins with a review of the arrow plot. Dips fit one

of five general patterns, each defined by the color of the pencil

used to mark them:

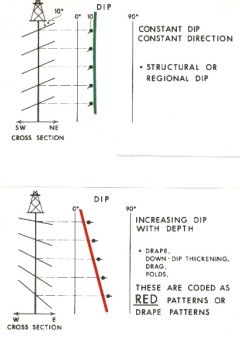

GREEN

PATTERNS: nearly constant dip and direction, representing regional

dip, sometimes called structural dip.

GREEN

PATTERNS: nearly constant dip and direction, representing regional

dip, sometimes called structural dip.

RED

PATTERNS: increasing dip with depth, representing drape, down

dip thickening,

RED

PATTERNS: increasing dip with depth, representing drape, down

dip thickening,

differential compaction, drag on faults, or folding.

differential compaction, drag on faults, or folding.

BLUE

PATTERNS: decreasing dip with depth, representing drag on faults

or folding.

BLUE

PATTERNS: decreasing dip with depth, representing drag on faults

or folding.

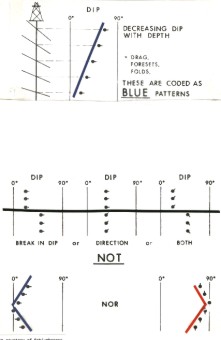

BLACK

PATTERNS: abrupt change in dip and/or direction, representing

unconformities, fault planes, or erosional boundaries between

stratigraphic units.

BLACK

PATTERNS: abrupt change in dip and/or direction, representing

unconformities, fault planes, or erosional boundaries between

stratigraphic units.

CIRCLED

PATTERNS or YELLOW PATTERNS: random dip angles or directions indicates

bad hole conditions, contorted bedding, fractures, slumping, or brecchia, sometimes associated with fault planes.

CIRCLED

PATTERNS or YELLOW PATTERNS: random dip angles or directions indicates

bad hole conditions, contorted bedding, fractures, slumping, or brecchia, sometimes associated with fault planes.

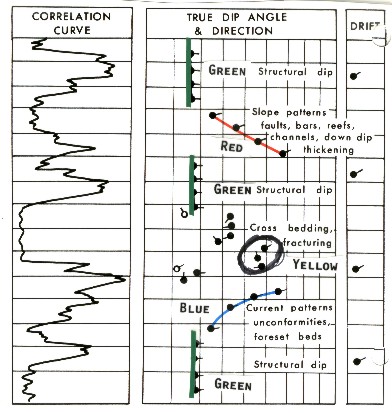

Colour patterns for dipmeter interpretation

The

color assignments, namely green, red, blue, black, and yellow,

are purely arbitrary but have become an industry standard by common

usage. Appropriately colored pencils or ink markers are used to

join dip arrows to emphasize the patterns. The five patterns are

illustrated schematically above. The features associated

with each pattern are listed on the illustrations.

Dipmeter pattern colour codes with stick diagrams

All

but black patterns should have roughly constant dip direction,

or else they are not real patterns. An exception is a pattern

that passes through zero or ninety degrees, where dip direction

will reverse.

To

begin analysis, start at the top of the log (or somewhere above

the zone of interest) and draw in the green, red, blue, black.

and yellow patterns, in the order listed. Be careful not to cross

a major change in dip direction with one of these patterns, unless

it is an exception as described above. Remember that such a change

in direction is normally a black pattern.

Join

arrows which are fairly close in depth. The end of a blue pattern

can be the beginning of a red pattern and vice versa. Not all

the results need to be included in every pattern. You may decide

some are due to noise, rough hole, or minor stratigraphic events

embedded in a larger structure.

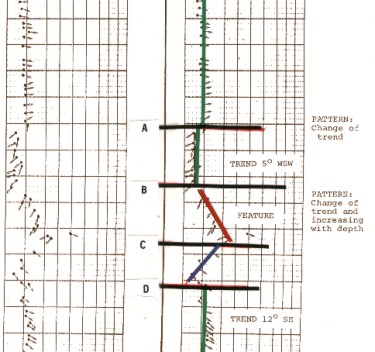

In

the example below, the top half of the log shows a trend

of dips at 9 degrees downward to the east - a GREEN pattern. The

horizontal line at "A" indicates a break in trend -

a BLACK pattern. This is followed by another GREEN pattern, indicating

regional dip of 5 degrees to the west south west below an unconformity

at depth "A". This is followed by a RED pattern indicating

drag above a fault. The fault plane is at or slightly above point

"C". This is followed by the reverse drag on the down

thrown block - a BLUE pattern, lying above another unconformity

at point "D".

Example of colour coded dip patterns

Although

we have described a plausible interpretation in the above description,

it may not be the only interpretation. However, it is not necessary

or even practical to analyze the meaning of all the patterns at

this stage - more than one interpretation is possible for all

patterns. For example, the event at "C" could be a stratigraphic

feature or another unconformity. We need to look at the open hole

logs and other well data.

For

structural interpretation, you may have to ignore stratigraphic

dips. This involves drawing the patterns through dissenting dips

in the sandstone layers. This is called macro-colouring as opposed

to micro-colouring, used in stratigraphic analysis.

For

stratigraphic work, do not join points across a dissenting dip.

The dissenting dips are the clues to stratigraphic changes. Join

arrows of about the same dip direction. The greater the dip magnitude,

the more similar the azimuths should be. Conversely, when very

small dips are considered, the azimuth can vary up to 90 degrees.

Keep

the scale of features in mind. Structural features may encompass

hundreds or thousands of feet of data. Stratigraphic features

may be superimposed on the structural patterns, and encompass

only a few feet to a few hundred feet. However, drape over reefs

and differential compaction may persist over several thousand

feet, and these features are associated with stratigraphic traps.

Red patterns associated with faults and unconformities tend to

show greater variations in dip magnitude over smaller vertical

intervals. Blue patterns associated with sedimentary structures

are usually short (up to a few feet on the vertical scale), whereas

the patterns that are a reflection of faults and unconformities

generally persist over much longer intervals.

|